Tasked by the City of Boston to lend a set of fresh eyes to the growing problem of climate change, the student team was asked to explore two primary questions and share their findings with the city:

- How might Boston best protect its most vulnerable areas, and their respective citizens, from ever-increasing stormwater runoff?

- How might the city best fund such mitigation strategies without unfairly burdening those with the least means?

Sebastian Agignoae (Harvard Kennedy School ‘22), Brian Cain (Harvard Kennedy School ‘22), Sasha LeFlore (Harvard Kennedy School/Stanford Graduate School of Business ‘22), Kyle Miller (Harvard Graduate School of Design/Harvard School of Public Health ‘21), Shruti Nagarajan (Harvard Kennedy School ‘22) sought solutions that would promote both environmental and financial equity, especially in neighborhoods with the greatest disparity.

“You walk around a place like Cambridge, and you see stormwater management tools implemented everywhere, but then you go to a place like East Boston, and those tools aren’t there,” said LeFlore. “So the question becomes, how do you develop the infrastructure to minimize the impact of stormwater management in those communities?”

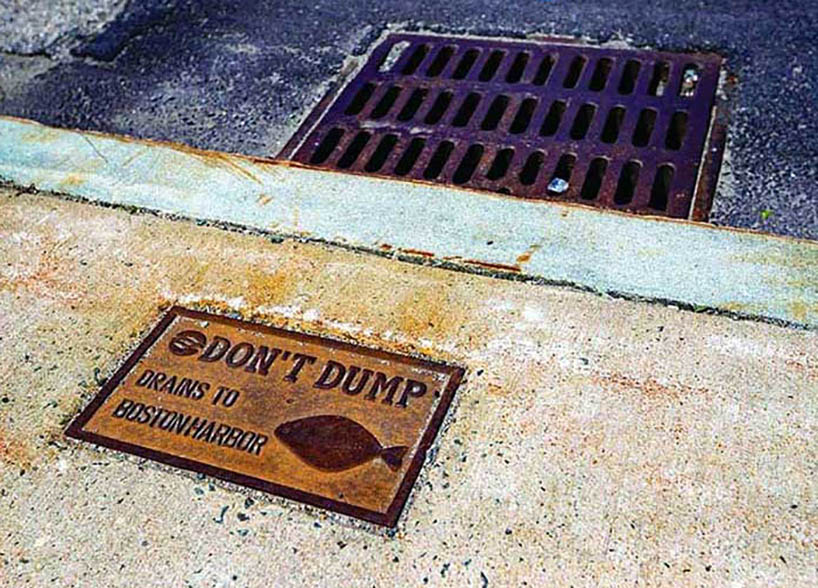

On a fundamental level, the problem with stormwater runoff – whether that be rain or melting snow following a storm – is the longer it stays on an impermeable surface like pavement, the more damage it does.

“Stormwater degrades the property and the infrastructure,” said Agignoae. “But it also degrades the health of the residents in these communities.”

The solution?

“You want to retain stormwater where it falls,” said Cain, who is a CPA and led the team’s financial model development. “You want to catch it and hold it there and very slowly let it go back into the ecosystem instead of letting it flood down the street.”