The practice of non-objective painting, once the leading light of Modernism, has over the past few decades gradually wizened to a position of gray eminence, still respected but increasingly overshadowed by an onrush of new media, new strategies, and new aesthetic concerns.

During the twentieth century, total abstraction was avant-garde, a heady revelation and revolution that succeeded due to its overwhelming cultural relevance. Artists had at long last found what they considered to be a universal visual language, liberated from narrative, anecdote, description, and slavish devotion to stultifying particularities – a language grounded in deeper realities that could reflect the underlying structures of human thought, perception, emotion, and society. Two distinct dialects emerged. One, geometric abstraction, reified a mechanistic Cartesian model wherein all phenomena could be somehow plotted along x, y, or z axes. The world it described was rational, ordered, quantifiable, and capable of balance. The other, biomorphic abstraction, derived from Freudian free-association and attempted to reveal the irrational, visceral, unpredictable, and messily biological structures of the psyche and its larger projections onto culture-at-large. Thus, many of the great striving dualities of the twentieth century mind were played out in paint, in an exciting dialogue between competing abstract styles.

Times have changed. Paintings of orthogonal planes or squishy organs no longer adequately express our perceptions of life as lived (and thought about) at the very beginning of this century. Non-objective painting, to survive past a current and unfortunate phase of irony, mannerism, and decorative exhaustion, must stop looking backwards and inwards, and start finding its structural underpinnings in more relevant issues.

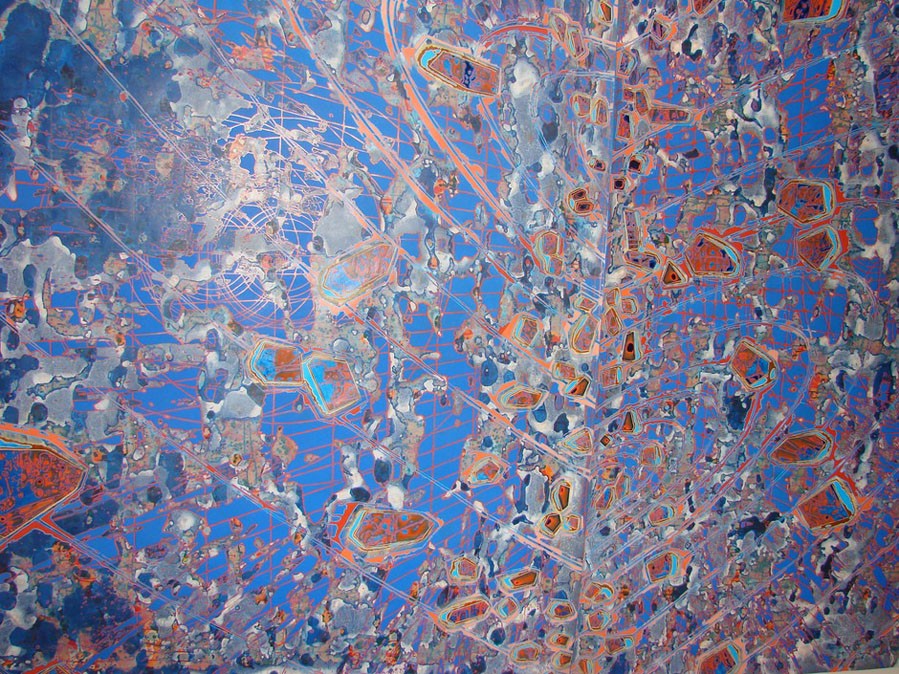

Sarah Walker is chief among a new generation of artists who just might rescue non-objective painting from an impending art historical obituary. These painters link their vision and practice with new and newly understood realities that will circumscribe life in the twenty-first century: genetic mapping and engineering, neurobiology, the new physics (including quantum mechanics, string theory, and chaos theory), fractal geometry, information theory, and the virtual realms of the computer and the Internet. These recent developments provide new lenses – indeed fresh eyes – with which to see the world.

Walker concerns herself primarily with intertwined and ever-collapsing new conceptions of physical space, mental space, and virtual space. The spaces that we perceive in the cosmos, through the computer, and within our own brains are of course projections of our own neurological hard-wiring. But we’ve accessed new files, so to speak, and our constructions of space now significantly transcended models based on the rigid mathematical grid or the unbridled outpourings of the subconscious. These new files are Walker’s territories.

Her paintings are at once compositionally clear and dazzlingly complex. Their grosser aspects, for the most part, consist of a central and vertical undulating feature set against broad modulated horizontal passages or against a single roughly monochrome ground. Shot through all of this are multiple arrays of smaller images, usually nested or linked sets of quasi-geometric nodes or shattered planar areas. The viewer seems confronted by a space, or a place, but one marked by a dizzying instability.