“I had seen how hard people have to work to run a small business, how many years it takes to become successful, and it was just a shame to think that all these people working 12 hours a day, seven days a week for years and years and years, could have it all dashed because of the pandemic,” he said. “If I could do something to help out someone in a tangible way by plugging into a project like Salem, that’s what I wanted to do.”

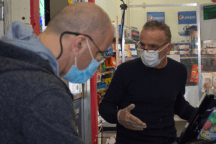

It was exactly that tangible nature of the project – the ability to look a struggling small business owner in the eye, talk about his or her needs, then quantifiably provide results – that struck Khoury as unique to local government work and particularly appealing.

“It was really cool to see the survey results in aggregate, but also to have those conversations to draw on,” he said.

He helped define the system that would be used and was primarily responsible for diagnostic assessment of the findings.

There were trends (providing space for outdoor dining was critical), there was low-hanging fruit (securing PPE was simpler and far more cost-effective for the city than the businesses) and there were surprises (city-sponsored restaurant delivery was not a priority). Through it all, there was an ability for the Dream Team to pivot quickly and tailor the plan to changing needs.

“If we were looking at some of the data in one way, and then heard from someone else that made us think if it a little differently, we would change strategy, or we would go a little deeper to see if it was the way other businesses felt,” he said. “Those conversations mattered in a way that I might not have believed.”

It especially mattered to those who were counting on the help. The plan rolled out and included things such as hundreds of pandemic kits, provisions for outdoor dining space, access to funding resources, and a marketing which emphasized shopping locally and highlighted safety. It had three stages: preparation, opening, and long-term viability.

The gratitude among the business owners at large, Khoury said, was very evident.

“It was really heartening to see how many people were in tough situations and were still very appreciative that they had input, and that somebody was trying to look out for them,” he said.

Khoury’s Rappaport Fellowship ended in June, at just about the time Salem businesses were re-opening, and he returned to Cambridge as an Economics teaching fellow at Harvard while he considered longer-term career options.

And that’s where it gets interesting. With the Rappaport Fellowship still fresh in his mind, his attention had shifted, at least to a small degree, from other parts of the world to this part of it. What had once seemed an unlikely path was growing more likely by the day.

The Fellowship’s namesake, Jerry Rappaport, has made a career of intensely focusing on the places where he resides – most specifically Greater Boston – and doing work there that later has the chance to echo and emanate. Following Khoury’s work in Salem, it’s a phenomenon that was beginning to ring familiar.

And it’s a phenomenon with enough appeal that, not long after leaving the Dream Team, Khoury earned a position with the Harvard Kennedy School Government Performance Lab, an agency which embeds its employees in state and local governments to improve systems and responses to various social issues.

It’s a job he likely wouldn’t have considered six months earlier.

“I didn’t think of myself as someone who was going to work in local government,” he said. “This was not my career track, and I do believe that if we cared about more about people in far-off places, we could do a ton of good.

“But I have a whole new appreciation for the fact that we’re all uniquely equipped to address the problems in our own backyards, which is a good way to get a foundation if we want to do something far away later.”

And if other options don’t work out, Khoury has a big fan in the city where he spent part of his summer.

“I wish I could hire Alex,” Mayor Driscoll said. “I’d hire Alex in a second.”